This post first appeared on Picture Book Den’s Blogspot.

HALF OUR ANIMALS ARE MISSING!

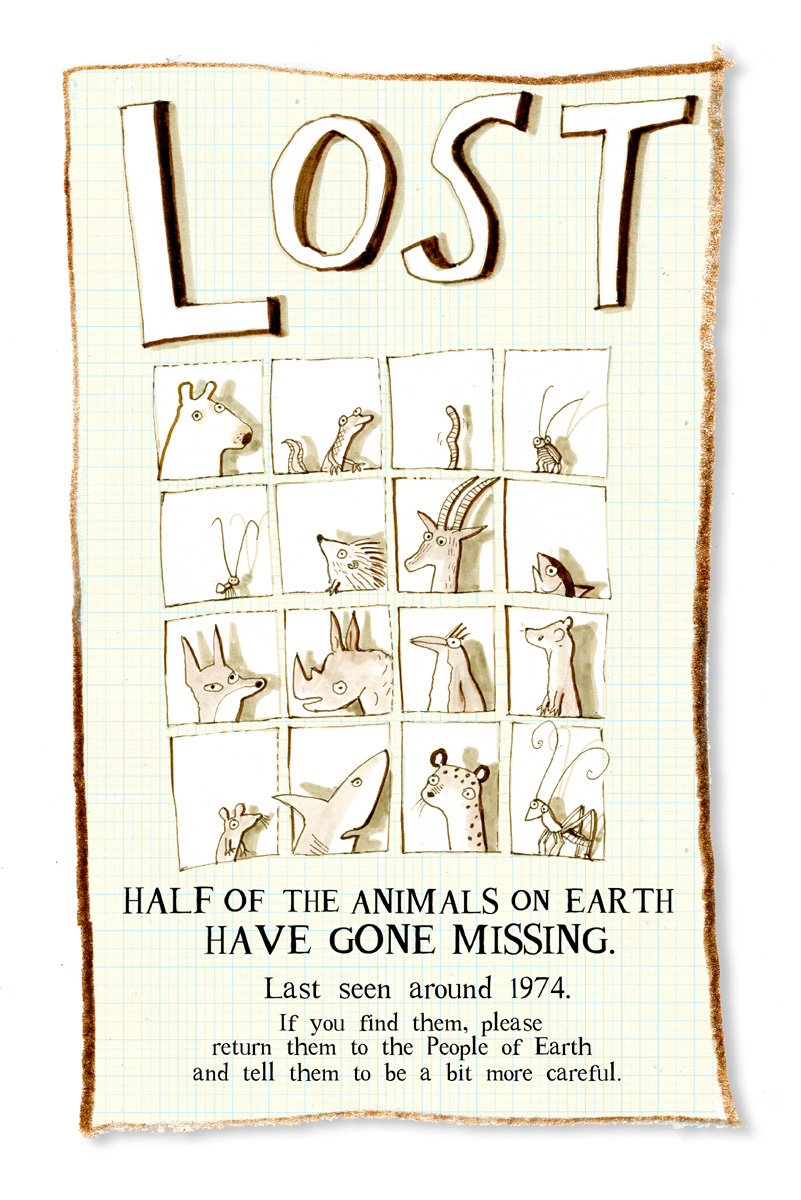

A few years ago an announcement came out in the news. According to the WWF Living Planet Report, since the 1970s more than half of the wild vertebrate animals on Earth had quietly disappeared. Half of our animals are missing! – how could we have been so careless? And those were the big, visible animals. In a more recent study from Germany, 75% of flying insects – the insects on which everything else depends – were found to have vanished in 25 years. Things are quietly disappearing. Why are they disappearing?

A few years ago an announcement came out in the news. According to the WWF Living Planet Report, since the 1970s more than half of the wild vertebrate animals on Earth had quietly disappeared. Half of our animals are missing! – how could we have been so careless? And those were the big, visible animals. In a more recent study from Germany, 75% of flying insects – the insects on which everything else depends – were found to have vanished in 25 years. Things are quietly disappearing. Why are they disappearing?

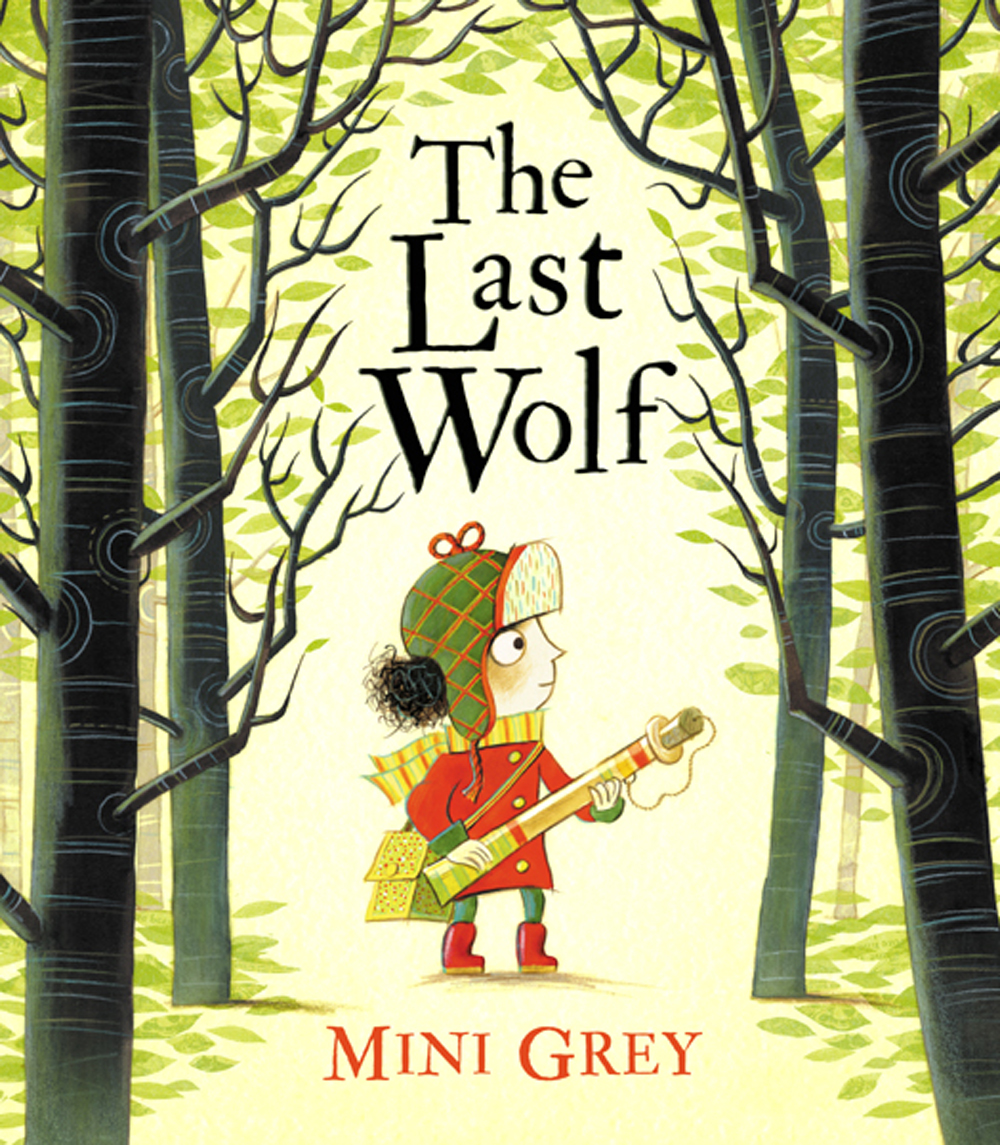

THE LAST WOLF IN ENGLAND

The story of The Last Wolf started with Red Riding Hood. I wondered: what if, instead of taking that basket of goodies to Granny, Red is in the woods because she wants to catch a wolf. But could she actually find a wolf? In England, wolves were probably extinct by 1500, and the last wolf in Scotland may have been killed in 1680. There were once wolves, lynxes and bears, but we’ve lost all our big predators now and become a land of more Wind in the Willows-sized animals.

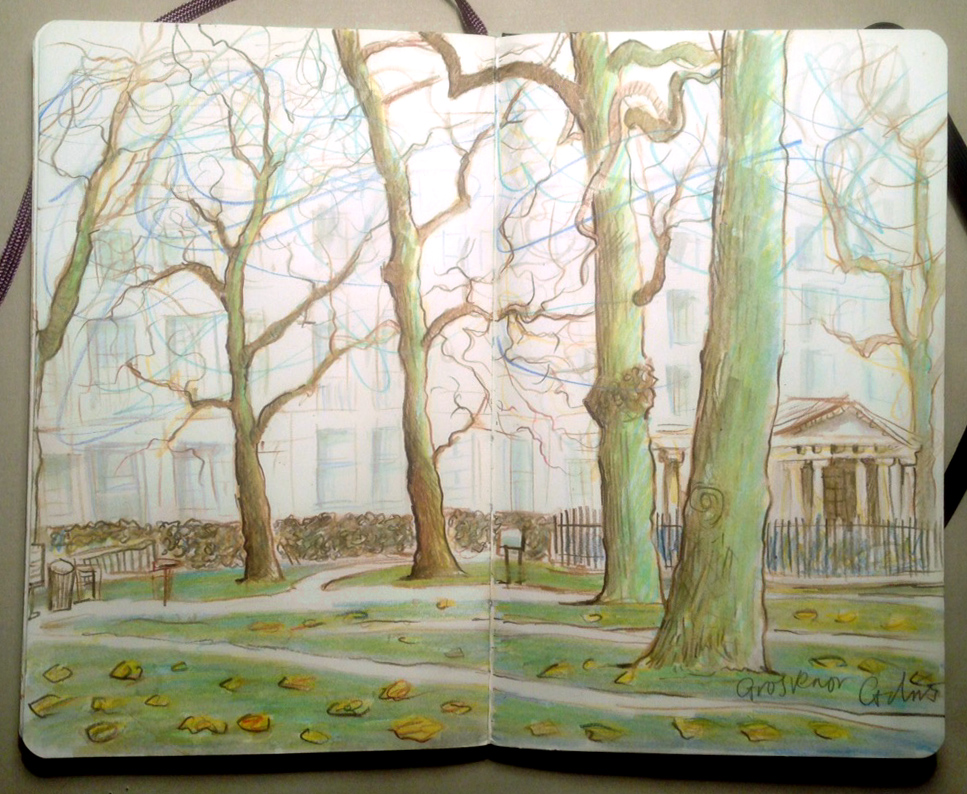

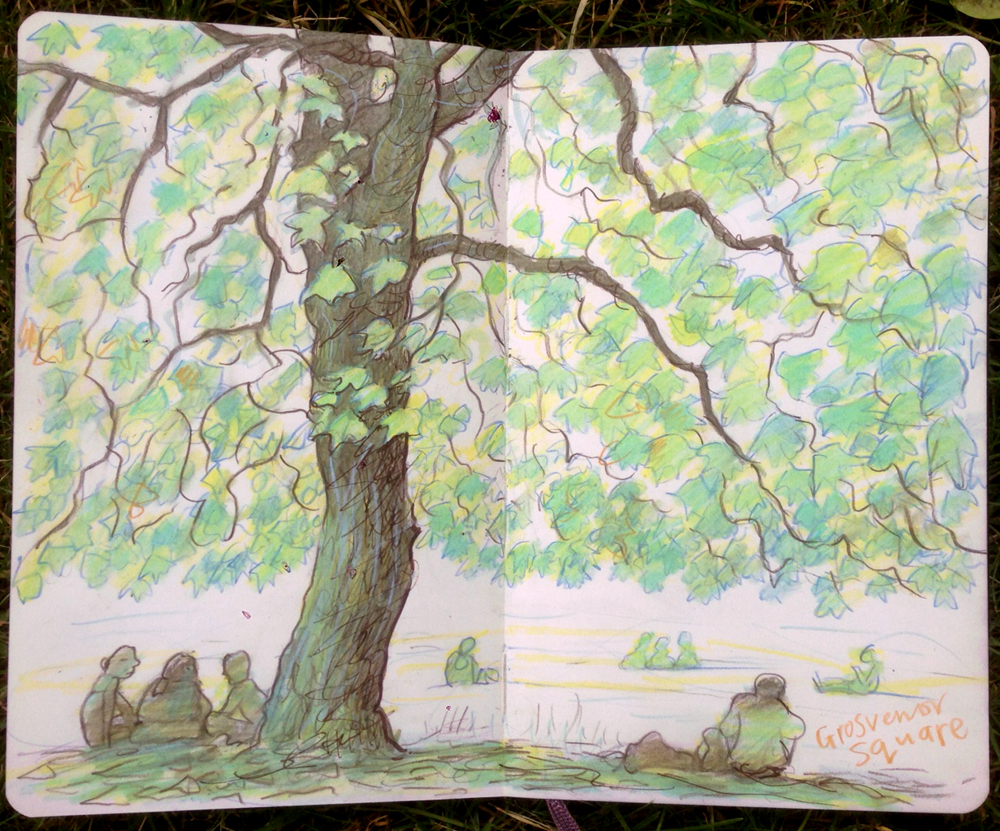

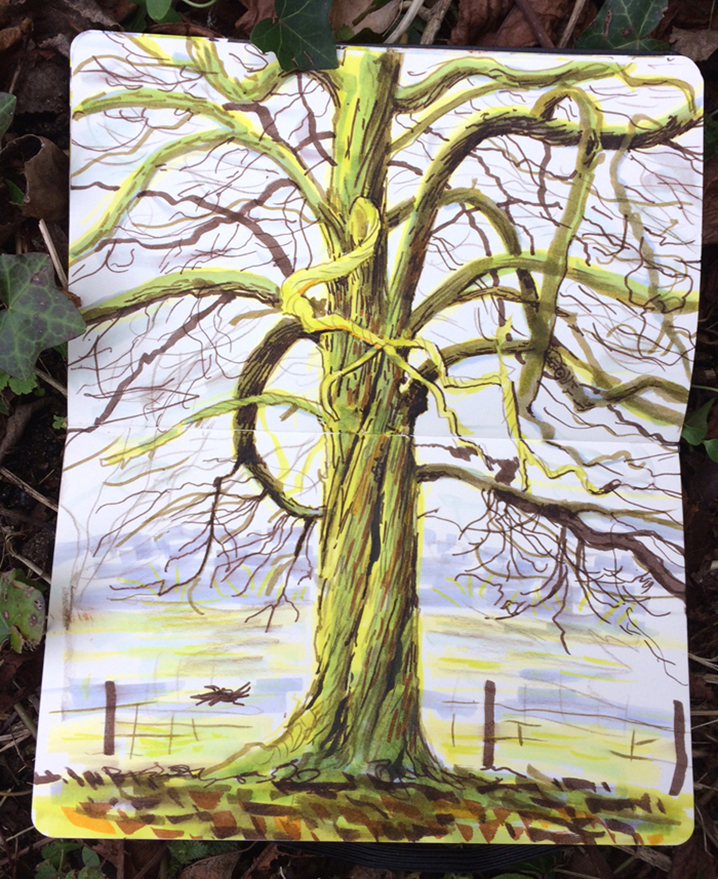

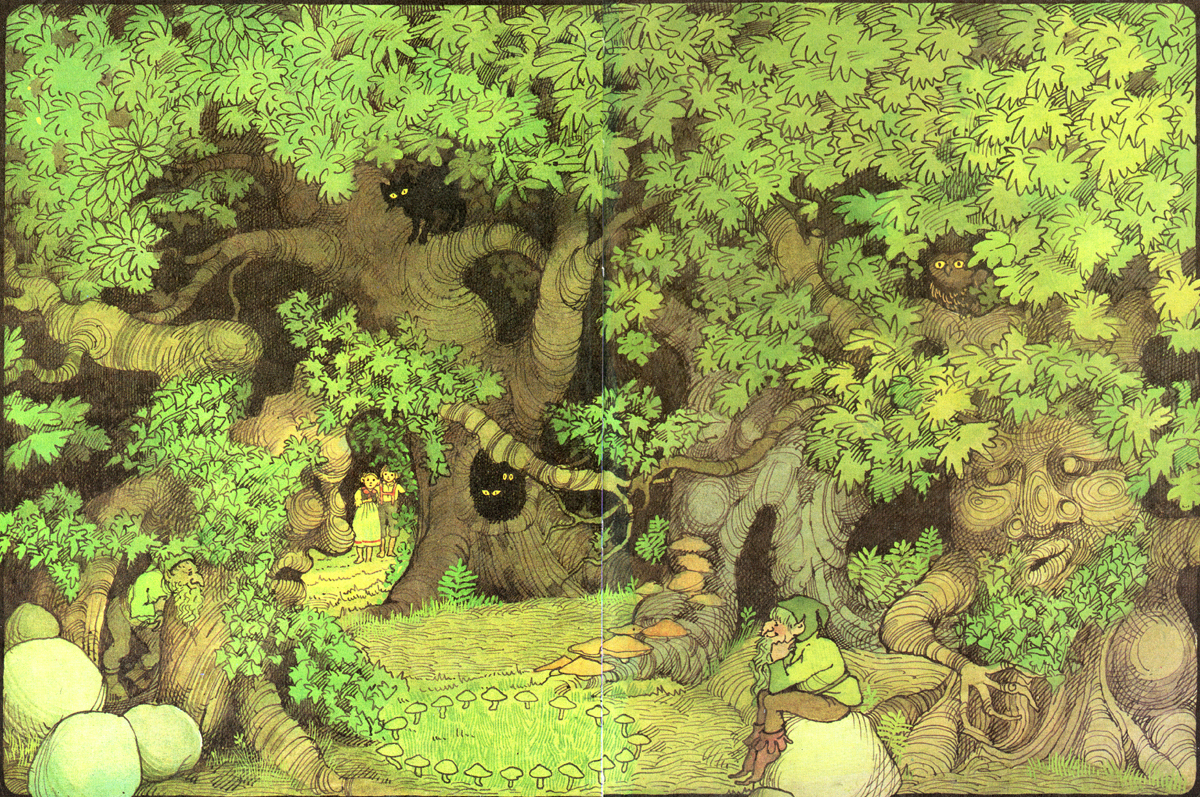

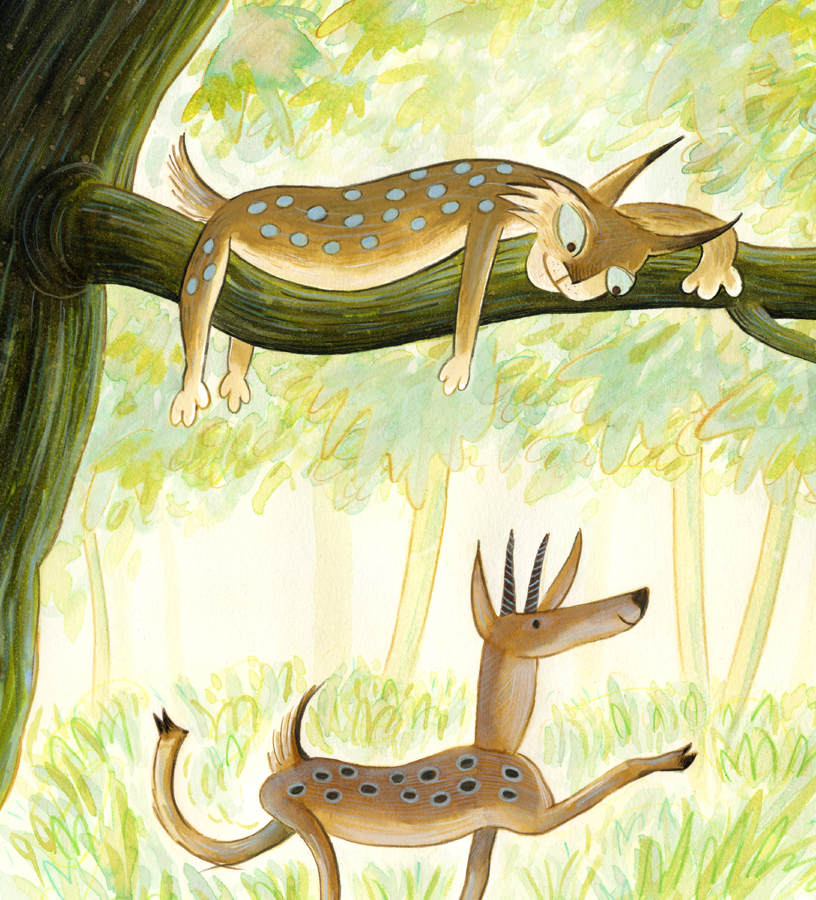

But walking in the woods can make you remember that the woods could once be dangerous places, where the unwary and unwise could get into trouble. It’s easy to be hidden in woods. Near where I live in Oxford are the wonderful Wytham Woods, which have been studied for over 60 years and where you can walk around and see big old trees full of lumps and crevices, which are also fun to draw. When I was thinking about the story of the Last Wolf I liked walking in Wytham Woods and imagining a wolf was there, and drawing the big old trees.

Near where I live in Oxford are the wonderful Wytham Woods, which have been studied for over 60 years and where you can walk around and see big old trees full of lumps and crevices, which are also fun to draw. When I was thinking about the story of the Last Wolf I liked walking in Wytham Woods and imagining a wolf was there, and drawing the big old trees.

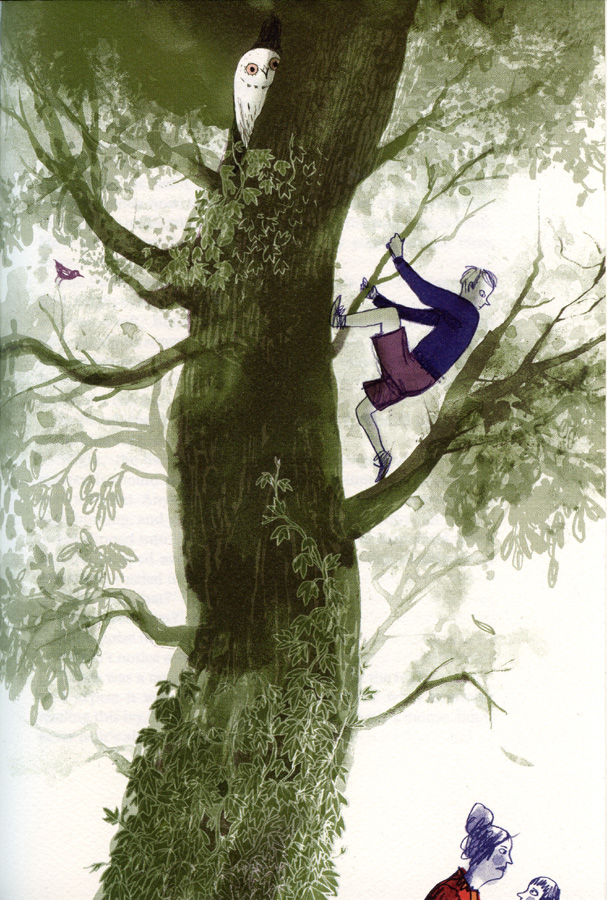

I collected my favourite picture book trees – which started with these by Jenny Williams: Here are more beautiful picture book trees. This is from John Masefield’s The Midnight Folk illustrated by Sara Ogilvy:

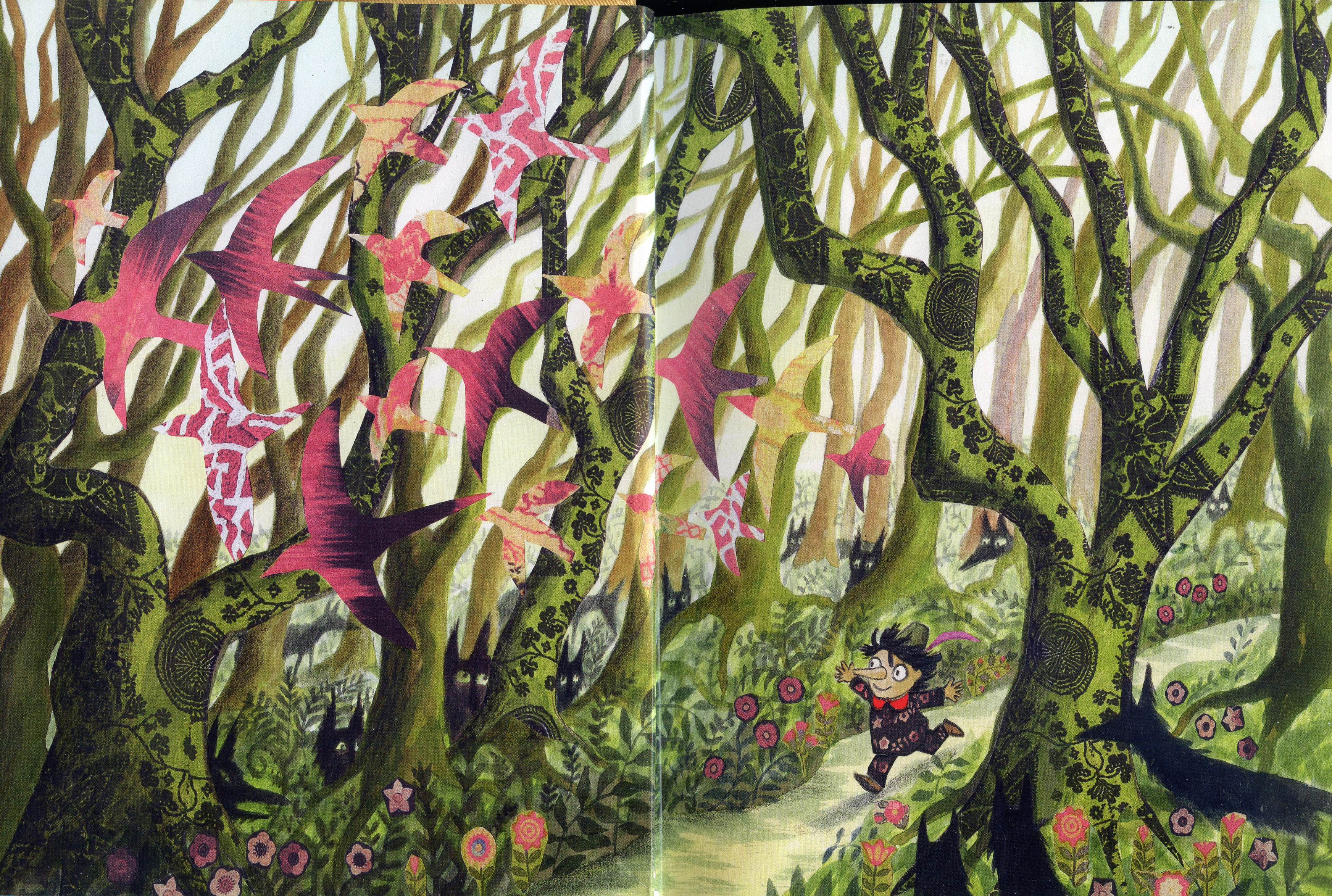

Here are more beautiful picture book trees. This is from John Masefield’s The Midnight Folk illustrated by Sara Ogilvy: and these wonderful wolfish woods are from Emma Chichester Clarke and Michael Morpurgo’s Pinocchio:

and these wonderful wolfish woods are from Emma Chichester Clarke and Michael Morpurgo’s Pinocchio: I kept these at hand for inspiration. Most of my previous picture books have been set indoors in the world of man-made things, so it was exciting to go venturing into the trees.

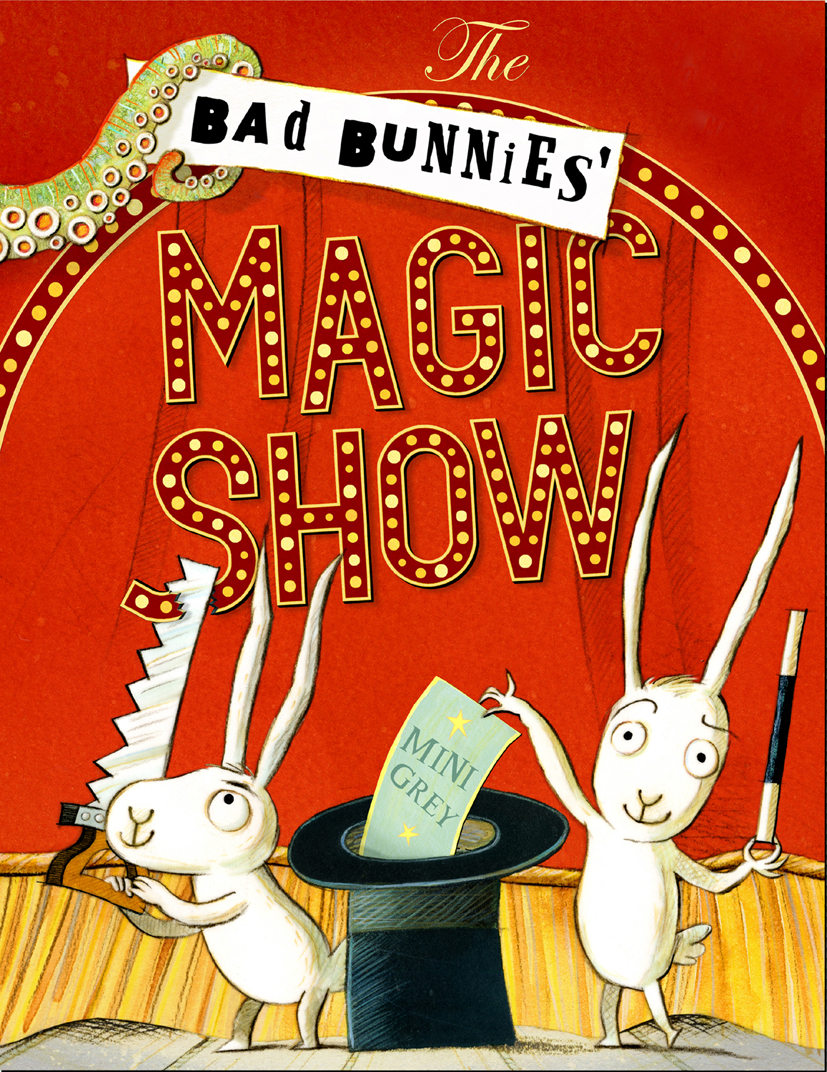

I kept these at hand for inspiration. Most of my previous picture books have been set indoors in the world of man-made things, so it was exciting to go venturing into the trees.

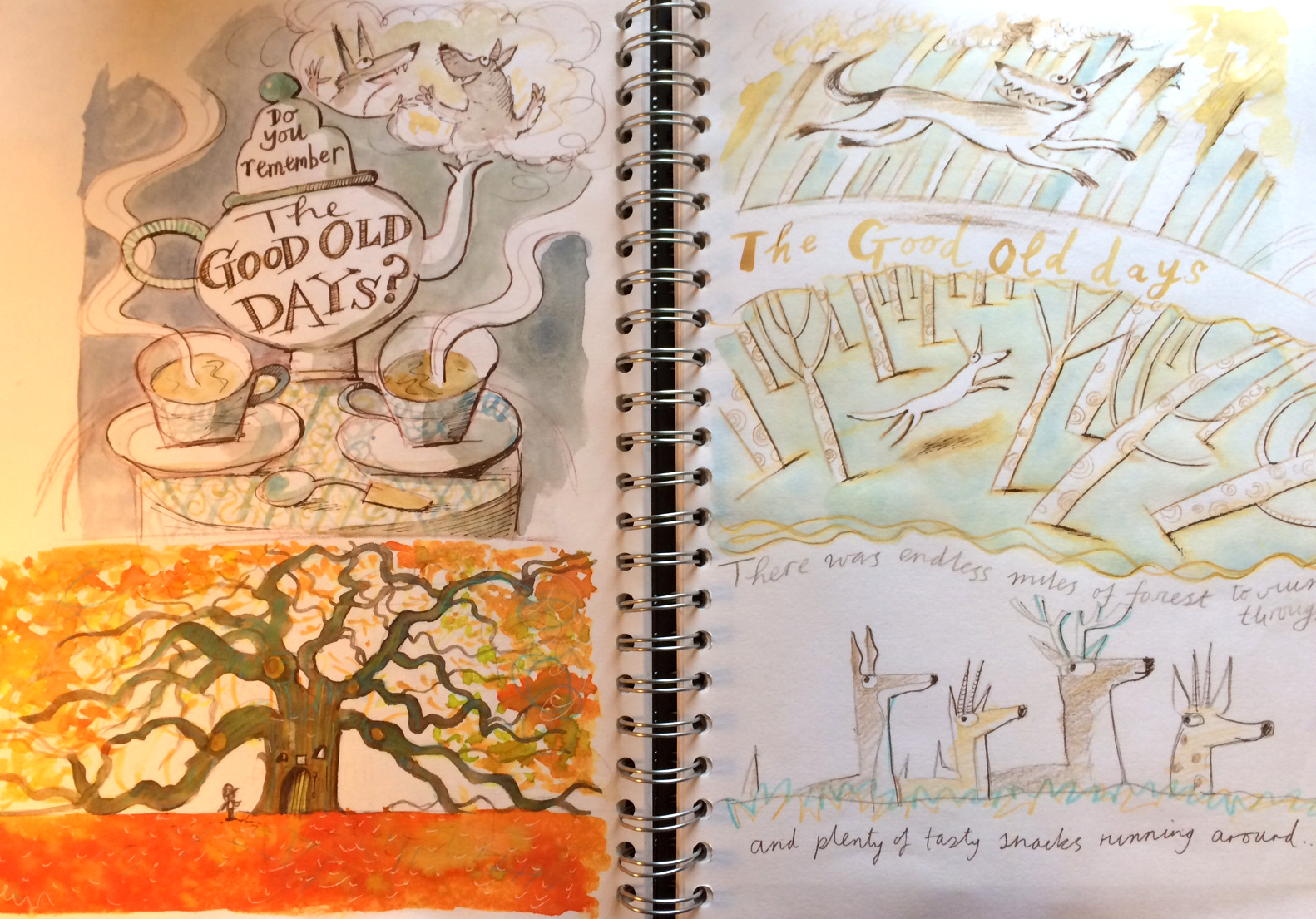

Here are some sketchbook pages from when I was working out the Last Wolf. I wasn’t sure how to end the story. I did want to begin and end the story with the Good Old Days forest at the beginning and the shrunken woods eaten into by houses at the end, but my wise editor Joe Marriott at Penguin Random House helped me to find a more hopeful ending.

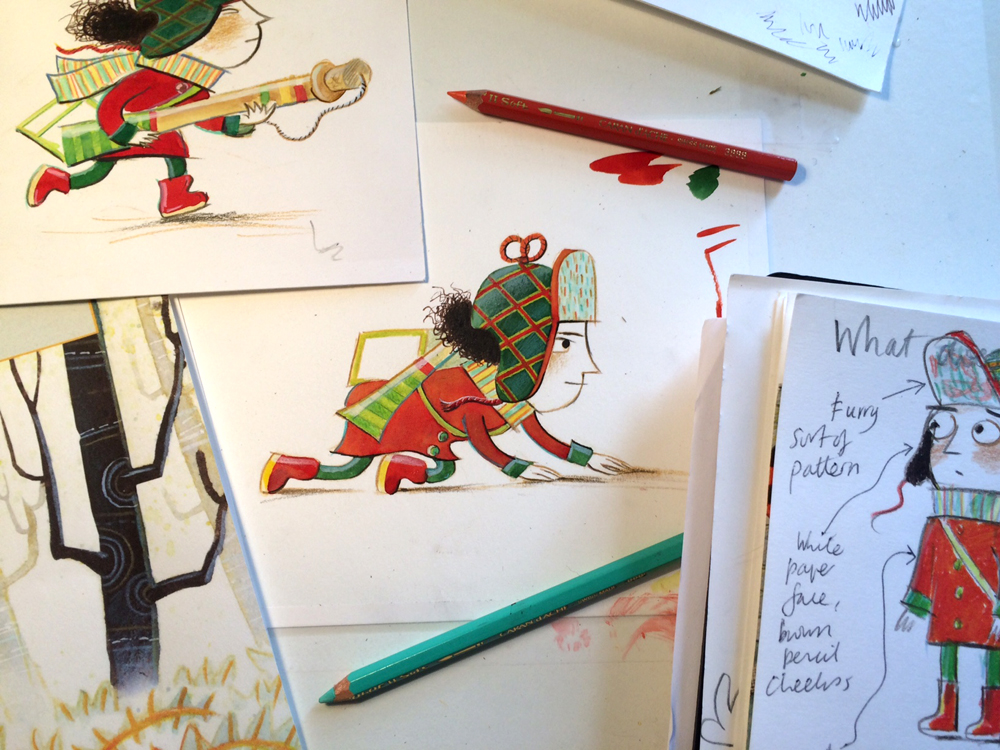

Here’s the bit in the book where Red meets the Last Wolf.

Here’s the bit in the book where Red meets the Last Wolf.

And now to….

And now to….

VAUCANSON’S DUCK

This is all that was last seen of Vaucanson’s Duck. It is thought to have been destroyed in a fire in 1879. The Duck was an extraordinarily lifelike automaton. It could quack and drink and eat duck-food, which it would then transform into duck-poo to the astonishment of everybody around. It looked like a living breathing bird. But the burnt remains of the Duck reveal the cogs and springs and cams which made this illusion of life happen.

It is thought to have been destroyed in a fire in 1879. The Duck was an extraordinarily lifelike automaton. It could quack and drink and eat duck-food, which it would then transform into duck-poo to the astonishment of everybody around. It looked like a living breathing bird. But the burnt remains of the Duck reveal the cogs and springs and cams which made this illusion of life happen.

ANIMALS AND US

In the usual human view of the world, it is divided into those that talk and those that don’t. This is very useful, because it means that those that talk can farm and eat those that don’t.

It is Rene Descartes I blame for this. Descartes (1596 – 1650) maintained that animals cannot reason and do not feel pain; animals are living organic creatures, but they are automata, like mechanical robots. Descartes held that only humans are conscious, have minds and souls, can learn and have language and therefore only humans are deserving of compassion.

He assumed animals were automata. But this is a big mix-up: automata – machines which create an illusion of inner life, but work by clockwork and cams – can only be made by humans. Only people make machines like this. Nature doesn’t work this way. In the animal world it seems feelings drive behaviour. Feelings give the impulse to act, and determine what that action might be. Feeling scared at a threat brings an impulse to run away. Feeling strong, brave or angry will make you act differently. If something behaves like it has an inner life – then, I argue – it probably does. If my dog behaves like it is scared, it is because it feels scared. If my dog is behaving like it is pleased to see me, then it must be because it feels pleased to see me (I hope!) Rene Descartes drew up the drawbridge, made the world into Us and Them, human and non-human. The non-human can’t talk, so doesn’t have an inner life. And that means they can be owned, eaten and treated as slaves – all very economically useful. Only with the ideas of Charles Darwin did we start to see ourselves in the continuum of the tree of life, and take our place in the unfolding story of evolution. Picture books are a fantastic direct line to empathy and imagination –– where else can you explore what it would feel like to be an egg or a biscuit or a spoon?

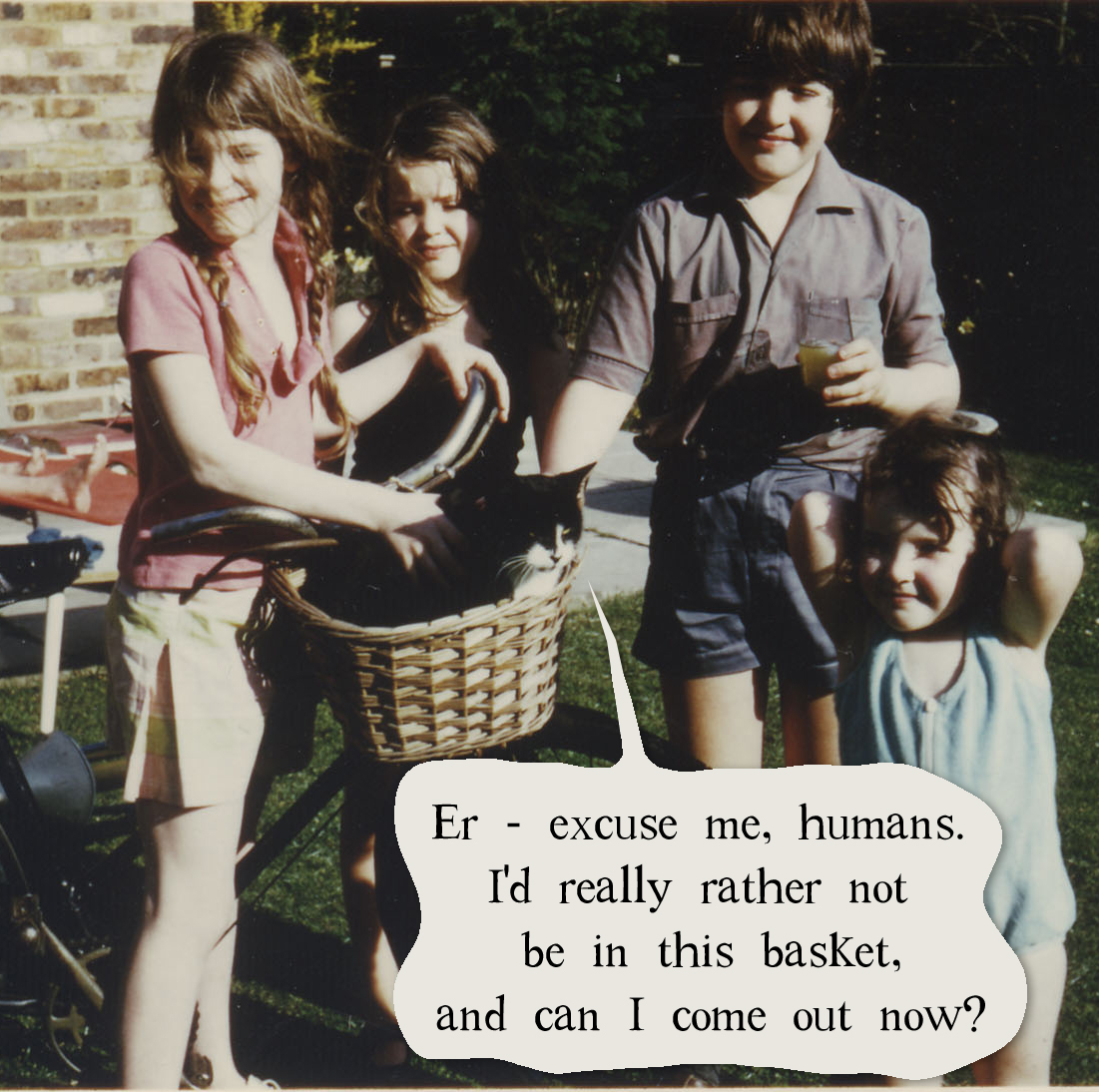

Picture books are a fantastic direct line to empathy and imagination –– where else can you explore what it would feel like to be an egg or a biscuit or a spoon?  But also the great thing about picture books is they are an arena where you can make anything you want happen. And one thing I’ve always wanted is to meet is an animal that could talk. But talking animals only really happen in books. The world of children’s books is crammed with talking animals – from Alice in Wonderland to Narnia to Philip Pullman’s daemons to Piers Torday’s Last Wild – talking animals are rife. Books are windows and doors into experiencing being someone else and that someone may be an animal.

But also the great thing about picture books is they are an arena where you can make anything you want happen. And one thing I’ve always wanted is to meet is an animal that could talk. But talking animals only really happen in books. The world of children’s books is crammed with talking animals – from Alice in Wonderland to Narnia to Philip Pullman’s daemons to Piers Torday’s Last Wild – talking animals are rife. Books are windows and doors into experiencing being someone else and that someone may be an animal. The legacy of Rene Descartes was to see animals as automata, giving an illusion of inner life, but not really having it. But automata are only possible because they are manmade – nothing in nature works this way. The inner lives of animals are worth imagining, what it must feel like to be them. Some animals end up being food. Would we be able to treat talking animals this way? It would seem a bit rude to eat someone who you could have a conversation with (see the Dish of the Day episode in Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy.) But maybe it is even ruder to eat someone you don’t know at all. An anonymous meat could well have had a terrible life. Maybe it is worth asking the question: Meat – Who did it use to be? Packaging is powerful stuff. It would be useful if meat packets could tell us more about the life of whoever is in the packet, so we could choose the one who had a good life before they were meat.

The legacy of Rene Descartes was to see animals as automata, giving an illusion of inner life, but not really having it. But automata are only possible because they are manmade – nothing in nature works this way. The inner lives of animals are worth imagining, what it must feel like to be them. Some animals end up being food. Would we be able to treat talking animals this way? It would seem a bit rude to eat someone who you could have a conversation with (see the Dish of the Day episode in Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy.) But maybe it is even ruder to eat someone you don’t know at all. An anonymous meat could well have had a terrible life. Maybe it is worth asking the question: Meat – Who did it use to be? Packaging is powerful stuff. It would be useful if meat packets could tell us more about the life of whoever is in the packet, so we could choose the one who had a good life before they were meat.

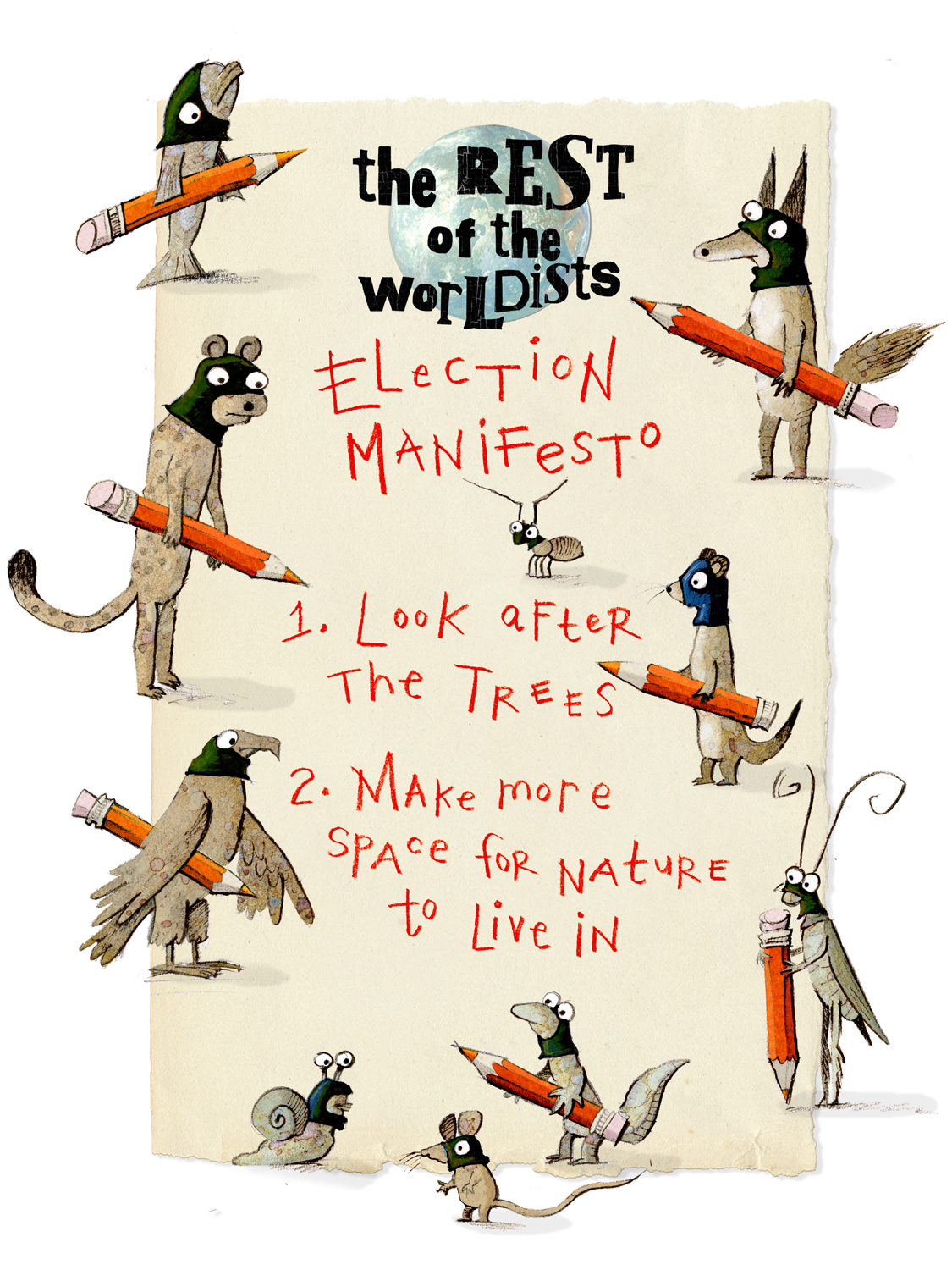

MORE TREES PLEASE  Red Riding Hood is a tale that came out of the terror of the forests – the ancient human struggle for survival against nature and predators. But things aren’t like this anymore – we’ve remade the landscape of our planet and its animals to support nearly 7 billion humans on Earth. It could be time now to change our Us and Them thinking. It always used to have to be ‘Humans first’, because we were small and the Wild was vast. But now the vast majority – some say 98% – of the mass of vertebrate land animals is us and our livestock. Could we give back a bit more space for the Rest of the World? We could include thinking about nature in everything we plan, and try putting a real value on our existing nature especially ancient woodlands. The amazing 4.6 billion year story of life on Earth – the complex long weaving of our life on Earth – is it OK to unravel and simplify this?

Red Riding Hood is a tale that came out of the terror of the forests – the ancient human struggle for survival against nature and predators. But things aren’t like this anymore – we’ve remade the landscape of our planet and its animals to support nearly 7 billion humans on Earth. It could be time now to change our Us and Them thinking. It always used to have to be ‘Humans first’, because we were small and the Wild was vast. But now the vast majority – some say 98% – of the mass of vertebrate land animals is us and our livestock. Could we give back a bit more space for the Rest of the World? We could include thinking about nature in everything we plan, and try putting a real value on our existing nature especially ancient woodlands. The amazing 4.6 billion year story of life on Earth – the complex long weaving of our life on Earth – is it OK to unravel and simplify this?

We can tackle this by framing everything we do in the context of nature, but also we have to step back a bit – leave more land unclaimed, leave the Antarctic Krill for the Antarctic animals. This needs regulation and legislation, otherwise a tragedy of the commons always happens. The National Planning Policy Statement of 2012 put ‘sustainable development’ (is that not an impossible thing?) at the heart of the planning system. Here’s my dictionary’s definition of ‘sustainable’:

Sustainable adj 1 able to be sustained. 2 able to be maintained at a fixed level without exhausting natural resources or damaging the environment: sustainable development.

So – sustainable development means development at a level which can be continued indefinitely without environmental degradation. If you systematically convert unbuilt-on land into built-on land so the overall balance of land-use changes – this is not sustainable if carried on indefinitely even at a low level.

There’s a new draft National Planning Policy Statement out for consultation right now. We should make sure that putting space for Nature is at the heart of everything we plan. Here’s how you can give feedback. (And also here.)

Trees are multi-level, they make habitats more three dimensional. Trees seem especially important in cities. The challenge is: can we create our buildings in sympathy with trees, plan around big trees, be generous and build with enough space for big trees? Can we value big old trees as special individual entities – to be valued like national treasures, like St Paul’s Cathedral? A big old tree gives vastly more to us than a young sapling. They are not interchangeable. We have to factor in time, put a value on time so it is not affordable to cut down a big tree. It seems that Sheffield City Council’s destruction of their street trees at the moment is demonstrating exactly how not to do things.

MAKING SPACE FOR NATURE

If you give animals space and habitat to live in they bounce back. Rewilding Yellowstone Park with wolves boosted the whole dimensions of biodiversity there, by returning a missing keystone species – changing the behaviour of their prey and enabling woodland to grow back. Pine martins, red kites, beavers are all coming back from the brink in the UK. Rewilding can make more for all of us by restoring a balance of predators and prey and a more complex natural world.

Every little bit of wilderness helps.

Here’s a useful cut-out-and-keep Wild Verges Award – if you see a particularly lovely roadside verge of cow parsley and wild flowers later in the year you could award it to the council concerned. Or give it to your own garden.

PS: The Last Wolf is out now, published by Penguin Random House. Catch it if you can!